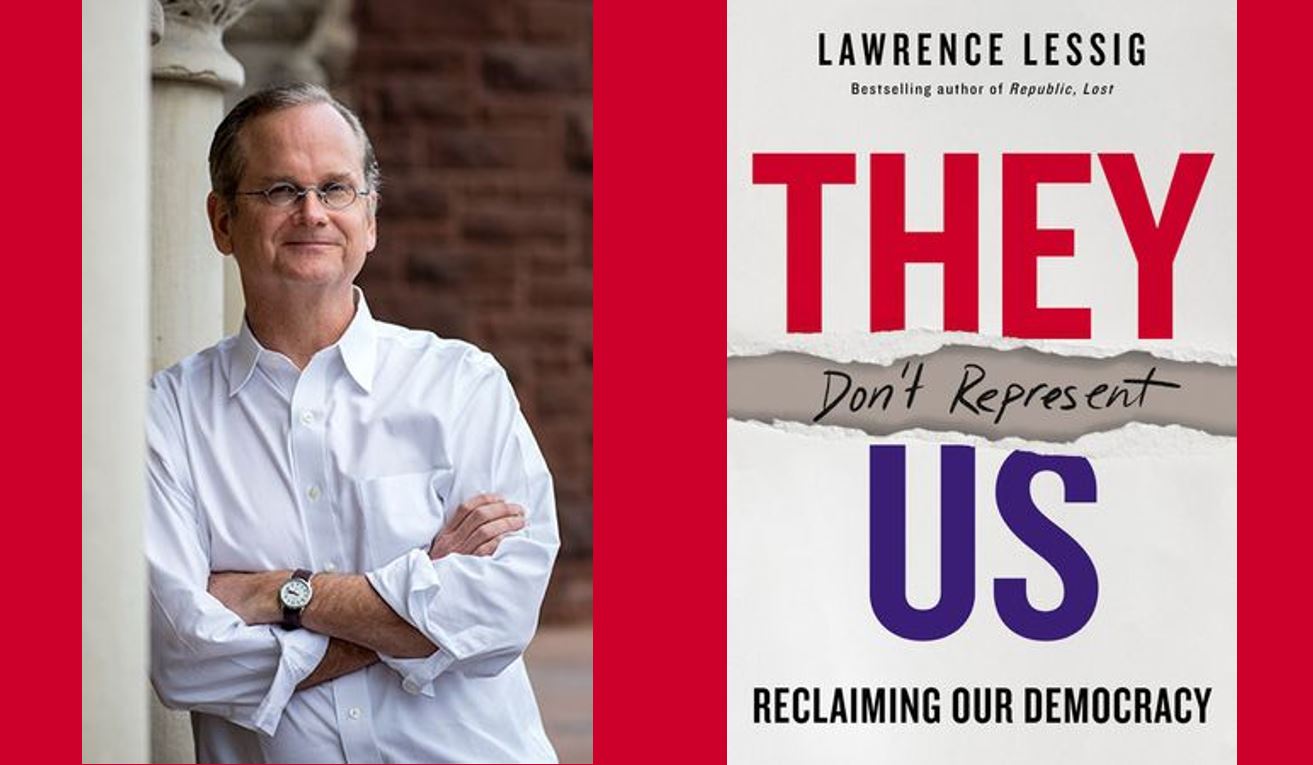

If we had 20 years to solve the problems of American democracy, what could we accomplish? If we don’t have 20 years, what should we do right now? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Lawrence Lessig. This present conversation focuses on Lessig’s book They Don’t Represent Us: Reclaiming Our Democracy. Lessig is the Roy L. Furman Professor of Law and Leadership at Harvard Law School, host of the podcast Another Way, and co-founder of Creative Commons. He has received numerous awards (including a Webby Life Time Achievement Award, the Free Software Foundation’s Freedom Award, and the Fastcase 50 Award), and was named one of Scientific American’s Top 50 Visionaries. He is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the American Philosophical Society, and the author of 10 books, including Republic, Lost.

¤

ANDY FITCH: Your preface’s opening paragraph provides a litany of 21st-century government dysfunctionalities: from our sluggish climate-change response, to our complacent reliance on an overpriced yet insufficient health-care system, to our grade of “D” on infrastructure quality, to further tax cuts for the rich apparently leaving any potential solutions to these problems underfunded for a long time to come. But before we get more detailed on any of those particular topics, could you sketch a few generalized vectors for how our constitutional structure and our recent political culture have taken us to this point? Which types of socio-economic-environmental concerns has US governance and/or US civic culture never excelled at addressing? Which types of concerns have we lost our knack for addressing (at least for now)? Which types of concerns might tech-driven innovation have made impossible for existing governmental mechanisms ever again to address — barring some recalibrating Article V convention? And which types of concerns might we finally, for the first time, find ourselves willing and equipped to take up?

LAWRENCE LESSIG: Political scientist Francis Fukuyama maps the way the American Constitution creates the conditions for a “vetocracy” — the pathology of any decision system in which a small number of people have the ability to block important progress or change. The framers gave us a system of separated powers, with various branches possessing the capacity to stop the government from acting. The framers did this because they wanted to ensure a broad consensus before the government acted. Even in the best of times, that system makes governing difficult.

But then in They Don’t Represent Us, I identify two more problems with our Constitution as it has evolved that make governing even more difficult — maybe now impossible.

First, the framers gave us a representative democracy. But we’ve allowed that “representativeness” to be corrupted. Whether through money in politics, or gerrymandering, or vote suppression, or the Electoral College — all of these corruptions render us not represented equally, which means all of these institutions give some people more power than others. Those more powerful sorts have more power to veto change. That’s why the most powerful in America today (drug companies, oil companies, insurance companies, you name it) can use the system to block real change.

Second, we have evolved a democracy that takes seriously the views of “the people,” as expressed in polling, just at the moment when “the people” have become so fragmented and polarized and misinformed as to be embarrassing. This too feeds vetocracy. You can always frame a political discussion today so that at least 30 percent of the public expresses fierce resistance to the idea being advanced. That resistance in turn terrifies the elected representatives into doing almost nothing.

Taken together, these two basic problems of representation make Fukuyama’s vetocracy a thousand times worse.

Your “Flaws” section’s opening sentence does tell us that one single flaw “cuts through everything that fails within this democracy: unrepresentativeness.” So could you start fleshing out the equality-of-representation principle underpinning our constitutional structure (and, you say, any republican form of government)? Where do you see this principle most conspicuously neglected or most problematically distorted at present? And what best outcomes could you foresee for a US political culture committed to refounding itself around this clarified principle?

At the very core of the idea of a republican government lies the ideal of political equality. Historically of course, the people for whom our Constitution offered political equality have varied widely. The framers didn’t care much about women and certainly not about African slaves as part of their equality-based democratic society. But those deemed to be proper political participants received this promise of equal representation.

Gerrymandering clearly violates this principle of equality. Gerrymandering draws electoral boundaries with the explicit purpose of giving certain people less power than others. Gerrymandered boundaries are designed for the direct purpose of creating inequality.

Or likewise, voting requirements or voting procedures get drawn in America today to make it harder for some to participate than others.

Likewise the Electoral College makes it so that so-called swing states matter much more than the rest of the country. If you live in Texas or Massachusetts, you don’t matter to the presidential campaigns. Again this produces inequality.

And so too (and most obviously) does our current mode of funding political campaigns produce striking and grotesque inequality. Members of Congress spend 30 to 70 percent of their time raising money from a tiny fraction of the one percent. Nobody can believe that this tiny fraction of the one percent possesses the same amount of political power as the rest of us. Of course they possess much, much more.

In each of these ways, unrepresentativeness has been injected to the core of our current system of government, and corrodes its republican foundations.

And I’ve asked about representation, rather than about active democratic participation, in part because your book announces its own ambivalence on this latter topic — most dramatically through your formulation that: “We don’t know… in a nonpolarized, sustained way…jack shit about policy, and we ought to be more open and honest…and proud…about what we don’t know.” Here could you start to parse having a democratic spirit perhaps, but not necessarily desiring all-encompassing direct-democracy decision-making processes (or even, for that matter, the election of countless relatively low-level officials)?

Good question. A core discipline of this book is realism about our everyday experience within modern democracy. And a core aim of that discipline is to make our participation as respectable as possible. We should not expect more from ourselves than we actually can give. Demanding more than we can give doesn’t show us respect. It shows us as ridiculous.

When I say that we (as in: the representative “we” called on the phone by Gallup pollsters) don’t know jack shit about policy, I mean that our lives, our interests, our hobbies, our loves, and our day-to-day connections with each other often have little to do with politics or policy. The idea that we should or could spend our time 24/7 (the way political junkies do) focused on every single issue… that’s just crazy talk. It just won’t happen. And when we organize our democracy around a form of public input that we know lacks depth or maybe even basic knowledge, we produce a democracy that will systematically embarrass itself.

Now, as you know from the book, I definitely don’t call for an end to democracy and for us to turn over governance to a clique of elites. I just think we need to craft (and always recalibrate) our democratic system towards a realistic understanding of how people will participate in it, and what we can expect from them when they do. When their natural way of engaging is insufficient, we need to craft different ways to engage them better.

So while my questions might focus on your conception of democracy less as an abstracted social vision than as a concrete “set of practices, embedded within institutions,” could you here touch on prospects for everyday agency that you do sense in individual citizens setting the tone for our democracy, tending to the ecosystem in which our political discourse takes place, recognizing the normative power that a self-reflective democratic populace possesses and perpetually needs to refine?

I’d say that we do need to become more reflective (and maybe more mature) about how we as a people keep getting played by both the politicians and the media. Both the media and the politicians have a deep interest in rendering us a bunch of crazies. They want to keep us passionate in our radical little corners, because that pays them so well. It pays politically because a radicalized base turns out more reliably at the polls. It pays the media because it gives your brand a more loyal and engaged and advertiser-friendly public.

We need to recognize that in both contexts this is their game. And we need to see that this game doesn’t do us or the country any good.

But we don’t need to devote ourselves to shutting down these games. We don’t need to give our busy lives over to condemning politics as it is. We just need different ways of engaging in the political process, less vulnerable to such agitating influences. We need to practice, first and foremost, the discipline of citizenship (not of Republican or Democratic partisanship, but something beyond each) if we want to make our democracy function well, rather than simply to make sure that the other side gets annihilated in the next election.

So I would consider these to be changes of practice, not of belief. We need different ways of engaging in politics, not a different political attitude. And I actually consider it much harder to change our basic ways of being within this democracy than it is to make a different choice at the ballot box. It’s possible to imagine a Democrat voting Republican. It’s harder to imagine inspiring a Democrat or Republican to engage with politics differently — more seriously, more reflectively, with more balance.

Of course you also present yourself as a “populist who does not rage,” but who recognizes a perennial “dynamic of populism throughout the ages…. When hope fades, anger flourishes.” You note the quickened pace and escalating stakes and increasing incapacities of our political culture to address such causes and such consequences of populism today. And you’ve described how our society’s own distinct dynamics of inclusion and exclusion always have left many Americans feeling under-represented by democracy. So within that broader context, how might we most persuasively channel today’s quite varied populist passions less towards restoring some relatively narrow band of citizens’ claims for proper democratic recognition, and more towards expanding conceptions of an empowered (if not necessarily over-involved) American demos?

Start with the basic populist project of forever expanding the scope of people included within the democratic system. Obviously, for the US, this meant starting from a very narrow slice — white, male, property owners. Then during the age of Andrew Jackson, we eliminated the property requirement. Then the 15th Amendment said, in theory, that race can’t be a reason to exclude people from voting. The 19th Amendment said the same about sex. Then the Poll Tax Amendment and the Supreme Court together removed any income requirement. Each of these steps expanded the range of people called upon to engage within our democratic elections. That overall progress is one part of a populist project.

Of course today we can debate about whether to include which immigrants, or whether we should include 16-year-olds. I myself would support adding participants from these relatively small slices of the population. But more broadly, I wrote this book to make the point that even though our democratic system now includes most of us, our system remains deeply flawed. It still funds its campaigns in a way that makes 99.9 percent of us irrelevant. It still allows state officials to effectively exclude voters they don’t like — whether by party or by race. It still relies upon the absurdly malfunctioning Electoral College.

We’ve won one kind of populist battle — to include practically all of us within the range of potential voters. But we’ve lost the war to ensure that all of us are equal.

In terms of that remaining 0.1 percent, again your own populism departs from populism’s most popular modes, by relying less on paranoid theories of billionaires pulling all the strings — and more on the disconcerting recognition that “Our actual system doesn’t benefit the elite (on balance)…it benefits no one”: with even exploitative rent-seeking schemes only serving certain self-interested players (at the expense of potentially more productive corporate competitors), with even political gerrymandering not stabilizing subdued single-party dominance so much as empowering the volatile extremes of both parties, with even outrageously expensive battleground-state presidential campaigns foregrounding the policy preferences of a relatively random demographic (based on the vagaries of a particular moment’s political map) rather than of the financial elite. So what most general case might you offer for why, even if America’s powerful class feels no antipathy to the plutocracy that Bernie Sanders describes, it should fear and oppose the type of dysfunctional vetocracy that Francis Fukuyama describes?

That’s right. I did consider it important for the book to push back against this kind of Bernie-style framing of the problem — because I believe this framing makes it so easy for so many to ignore how these problems affect them too. I don’t have any desire to speak to the unmet needs of 400 billionaires — if indeed, beyond love, they have unmet needs. But I do feel that when you frame this problem in purely class-based terms, you lose about half of America, who never really learned or wanted to think about America in this class-based way.

Look, I grew up a Republican. I am not anymore, but that’s how I grew up. And I’ve had any number of conversations with people who might be described as poor in American terms, or as economically and culturally isolated. But very few of these people would ever see America in the way that some of the more progressive Democratic candidates describe it. I don’t believe, either intellectually or politically, that you can simply point your finger at the billionaires and thereby convince most of America that you have identified the problem. More people believe immigrants are America’s main problem, not billionaires. That’s no reason to attack immigrants, of course. But it is a reason to move beyond class-based politics.

Instead, rather than class warfare, I advocate for focusing on ideals that we all claim to share. We live in a republic. That should mean a representative democracy. That should mean a system that represents us equally. But we don’t have that system, and because we don’t have that system, most Americans get screwed. Most Americans will remain screwed until we fix this corrupted democracy.

Regardless of who gets elected, we all lose out (even the billionaires) when our government can’t make progress. Just look at the past 10 years. It’s not as if, when Democrats win, Democrats fail to get anything done, but when Republicans win, the full range of Republican policies gets enacted. Neither side achieves much. This is the age of the stalemate. Of course we get tax cuts, at least for the rich — which is not surprising, given how campaigns get funded. But we get little more than tax cuts. No important issue (on the right or left) gets addressed sensibly under this broken and corrupted government. The collective failings of this vetocracy screw the left. They screw the right. And they screw everybody in between.

I also do want to pick up one of today’s more divisive political topics that you’d mentioned. I sympathize with your book’s suggestion that deliberate voter suppression, particularly when it produces glaring racial disparities, might rightly disturb and galvanize an advocate of American democracy as much as any present-day trend. But I also appreciate your recommendation that, rather than rail against white-supremacist political operatives, we might find it more useful to advocate reforming, say, America’s peculiar practice of having partisan elected officeholders, instead of nonpartisan career bureaucrats, administer our elections. Could you sketch an account here recognizing that a Democratic Party strategically incentivized to expand voting and a Republican Party strategically incentivized to suppress voting by no means offer moral equivalents — yet nonetheless arguing that we should tap “an idea of equality…even more fundamental” in order to make the most effective constitutional (and perhaps conversational) case?

I’ve spent a dozen years on the road talking about this issue. And outside the Washington Beltway, you don’t find many ordinary people (ordinary Republicans included) who will stand up and defend the idea that we should make it harder for some people to vote than for others. You don’t find many Americans affirmatively calling for a rigged system that screws some in order to benefit the party in power. In Washington, in the world of Mitch McConnell, no doubt you do find political operatives actively seeking ways to entrench a political system that benefits their party over the other. But Americans, as Americans, actually hate all of this partisan screwing around to screw the other side. Americans, as Americans, like a democracy that is actually fair.

Yet when I talk to people about the inequalities in this system, I’ll often find that it works better to appeal to our common principles, rather than to engage in a fraught discourse about racial inequality — which makes so many so defensive in so many ways. I believe that we can get a broader public commitment to building an inclusive democratic process if we can find a different language for that project. We need a language that itself is inclusive (not divisive), a language that builds on our common values as citizens (not one that foregrounds categorizations of some of us as the oppressor of others).

So, for instance, consider something that most mature democracies do: running elections with nonpartisan bureaucrats, rather than partisan election officials. Most Americans would consider that just common sense. Or consider an appeal to ensure that voting is equally easy for all Americans. Or a commitment to make electoral districts more fairly representative of our communities and states. None of these arguments need arouse defensive partisan ideology. And each of them contributes to this book’s basic discipline of asking: “Can we make arguments in a good-faith way that anybody should be able to accept?” I believe we can, and I believe that calls for voting equality provide one of the clearest examples.

Still in terms of how today’s corrosion of democratic institutions might prove even more problematic than the moral corruption of particular elected officials, and now specifically focusing on the destructive role that concentrated wealth does play in our legislative process, could you outline your First Amendment-related proposals less for banning extravagant PR campaigns designed to bamboozle the American electorate, and more for regulating how politically motivated spending infiltrates the daily operations of our supposed “people’s representatives”? Could you clarify how such financial influence plays out less through a process of “buying off” crooked politicians than through “the subtle nudge of perpetual fundraising, tied to the cuddling and collaboration with lobbyists”? And where amid those complex yet informal operations do you see grounds for constitutionally sanctioned reform?

It is certainly true that a core problem (maybe the most important problem) of the system today is that it requires representatives spending up to 70 percent of their time sucking up to a tiny fraction of America to fund their campaigns. That obviously has a pervasive and corrupting influence on our representative democracy.

But as you said, I don’t think that the politicians who get caught up in this kind of dependency are evil. I think they are human. In fact, if this constant dynamic of financial dependence didn’t make our political leaders inappropriately sympathetic to their donors, then we’d have to worry about whether they were psychopaths. Our species has developed an evolutionary sense of reciprocal obligation. If elected officials didn’t display that, then there’d be something wrong with them. Yet our present system for funding campaigns forces representatives to feel reciprocally obligated to a completely non-representative few. There is no reason to accept this corruption.

This plays out directly in campaign fundraising, and also indirectly through how super PACs operate. Senator Michael Bennet explains this well in his book. He talks about the corruption of inaction. And he describes how these super PACs just terrify our political representatives from taking any step forward — for fear of being trashed or clobbered by endless amounts of money. The super PAC doesn’t even have to spend this money to get representatives to react. It just needs to threaten to spend it. So here again there is a disproportionate influence of the super-rich (the people who fund these super PACs), which produces a fundamentally unrepresentative representative system.

So for prioritizing proactive electoral redesigns over reactive speech-related restrictions, could you describe a couple of your favorite potentially exportable and scalable models of speech credits, democracy coupons, democracy dollars, ranked-choice voting procedures — each in its own way incentivizing political campaigners to broaden their appeal? And/or could you make the case for why we shouldn’t be looking for universalizeable reforms, so much as figuring out from the ground up which type of electoral process best fits a given constituency?

The most obvious reform is to change how candidates for Congress raise money for campaigns.

Senator Kirsten Gillibrand, for example, has offered a really ambitious proposal to give voters, depending on the number of contests in a given year, up to six hundred dollars in “democracy dollars” — which you can donate to candidates to help fund their campaigns. Seattle does this in its local elections. And if each of us had a substantial sum to give out to candidates, many of these candidates would spend less time sucking up to a tiny few, and more time reaching out to the democratic many. You would have an incentive to rally thousands, tens of thousands, maybe millions of people (depending on the election) to turn over their democracy dollars to your congressional or senatorial campaign. Again, this change would end the completely understandable dependence that our political representatives now suffer in relation to the tiny few. And the Supreme Court would have no grounds for opposing this perfectly constitutional change.

That’s the change we need first. And any “reformer” who doesn’t prioritize this kind of basic change doesn’t deserve to be called a “reformer.”

And then, as to whether to prioritize local or national change: I certainly wish we had time to do this from the grassroots up. If we had 20 years to solve the problems of American democracy, I would favor launching different experiments in all 50 states, to figure out what works best. And, indeed, our most successful reform movements right now come from the state level. 2018 offered more successful state-level initiatives than any previous election in American history.

But I just don’t think we have that time. We can’t afford to wait 20 more years before addressing climate change. We can’t afford our current health-care system for 20 more years, or increasing drug prices for 20 more years. You pick your problem: we can’t afford to wait 20 years to solve that problem.

Policy wonks, of course, can offer a thousand good ideas for potential changes to bring about a more representative system. But in the political sphere, I think we need to keep it simple. We need to focus on the basic problem and fight to fix it. The core problem with our democracy today is that it is essentially unrepresentative. We should secure, finally, a representative democracy. We’ve never had it. So let’s just try it for once. Let’s see what happens with 10 years of a truly representative democracy. Let’s see if things get better.

This would mean making our democracy more representative in a variety of ways: fixing campaign funding, and gerrymandering, and the Electoral College, ending voter suppression, making the Senate a place of equal representation for every American. Some of these examples of unrepresentativeness we could fix tomorrow, and we should rally Americans around those fixes. And if presidential campaigns stopped saying things like “Listen to these 20 amazing ideas (from health care to free college) that I’m going to give you,” and started saying more clearly “You know that we can’t fix anything without fixing our democracy first,” then there’s a chance we could rally the nation to this essential change.

And here I do see reasons to be optimistic. We have 10 Democratic candidates calling for fixing democracy first of all. They promise that the first step they take if elected will be to implement a package of democratic reform. We might argue about which reforms should be in that package. But we haven’t seen presidential campaigns prioritizing structural reform in this way for at least 50 years. So maybe there’s still only a 20-percent chance of bringing about substantial reforms. But that’s an order of magnitude more than anything we’ve had recently.

Shifting now to how public speech also plays out through other everyday channels, I’d maybe start from your claim that every major political transformation in 20th-century America came about alongside the rise of a new communications medium telling us its own distinct narrative about ourselves. I’d continue with you placing the advertising industry, and more specifically our media’s (even our news media’s) relentless commitment to the business of monetizing attention, “at the center of all that ails us.” I’d bring in an acute post-broadcast present-day context in which the need to establish a niche-market audience incentivizes media-branding premised upon an instantly recognizable, unstintingly reliable, inevitably quite reductive and rigid worldview — certainly not preparing an informed democratic public to build constructive and reflective consensus.

Let’s start with a very specific problem facing us right now: impeachment. We’ve never had a presidential impeachment process happen in a media context like this.

With Andrew Johnson’s 19th-century impeachment, the only voices that mattered were voices of the political elite. For the public… who knew what they thought? Nobody polled them, because nobody could poll them. Scientific polling wouldn’t be invented for another 70 years. But as Brenda Wineapple describes beautifully in her book The Impeachers, the political elite struggled mightily with whether they should impeach Johnson. And in that system, the elite all listened to the same story. Based on that story, they figured out together what to do. Whether or not for corrupt reasons, they decided against conviction.

Richard Nixon’s 20th-century almost-impeachment was very different. But similarly, everyone was watching the same three networks, which told this story in a very mainstream, even-handed way. And so we, as a broader public, came to understand the story together, and we responded to the story together. Republicans began to lose faith in Nixon at the same time Democrats did — because both were watching the same news, and both were following this same story.

But with Trump’s impeachment, some of us will hear an entirely different story than others will hear. Whatever ends up happening, one side seems bound to feel uncomprehending outrage — whereas the other side will take the outcome as completely inevitable. One side’s media will ask its audience: “What the hell? How did this happen?” The other side’s media will insist this result was obvious.

Today’s media infrastructure is incentivized to keep us in these separate worlds. The most profitable way to compete within a fragmented media market is to focus on a partisan base, and feed it what it wants. Yet while that business model is profitable for them, it is incredibly costly for us.

I don’t know how a democracy decides fundamental questions when its public is so completely divided. I don’t know how we go forward without the capacity to overcome that division. We live, as Barack Obama has put it, in “different realities.” How does a democracy resolve questions when its public is divided into these “different realities”?

And so far we’ve only discussed more traditional information-media formats. So now in terms of social media, and in terms of the transformation from us watching TV to the Internet watching us, could you sketch some everyday lived conveniences that do seem to justify certain types of data-harvesting that, say, Shoshana Zuboff might distrust? And could we then pivot to where you might agree with Zuboff that Facebook’s and Google’s revenue-driven incentive to shape (not simply track) user behavior, to escalate (not just facilitate or enhance) user engagement, to keep giving us more of “what we want” (to the point that our access to a broader polity gets eclipsed), might make the gap between their business models and “the citizenship model of democracy… huge, and maybe unbridgeable”?

I want to move away from the simple frame of: are they taking our data or are they not? I want us to ask: what will they do with our data, and in what contexts? Personally, I love that Amazon or Netflix watches everything I do on their platforms, in order to recommend books I should read or movies I should watch. That’s great. That gives me more of what I want, and gives them what they want too. Everybody benefits from this type of “surveillance,” because this kind of “surveillance” is very different from a scary Stasi or FBI-style surveillance. This surveillance operates more like a butler than a spy — or so I imagine. I’ve never actually had a butler.

Me neither.

So I believe that certain forms of “surveillance” probably won’t disturb many of us, if we can move beyond that term’s more sinister connotations. But we do have to stay very, very vigilant about how even these more benign kinds of surveillance shape our individual perceptions and our society’s collective behavior.

I love the diversity of programming we get on television now. I’d say that the last 20 years have given us unambiguous improvement in the range and the quality of what we can see and experience and understand. But when we flip back to the democracy channel, we have to ask: what do these same ad-driven revenue models produce? Do they render us even more crazy, more isolated, more segmented? Does that have the consequence of making us less able to engage in democratic deliberation about our nation’s future?

I believe it does. And in my view, we should recognize these consequences and start to think through how we can prevent them.

I try to make this point with a basic analogy to food and diet. We all know how wonderful processed food tastes, and how addictive it can be. We also know how it harms our long-term health. Some people say: “Well, therefore, go and regulate processed foods.” And I will happily consider which regulations might work well. But first we need individuals to take responsibility for what they eat, and to recognize how a diet based solely on potato chips and buffalo wings will hurt them personally, and then hurt us as the society that pays the inevitable costs of their long-term ill health.

The same principle applies to our information diet. We can’t understand the issues driving an election if we only follow a Facebook news feed. Just like our bodies get hacked by junk food, our brains can get hacked by our Facebook feed. We have to take the personal initiative to step out from that influence if we want a boarder perspective. That responsibility is first on us individually, even if it is also on them.

As you know, I consider this to be the hardest problem to solve — because we don’t yet have any effective available tools for solving it. But without restoring some balance to our democratic deliberations, I fear that the damage social media will do to democracy will lead many to wonder whether we have any reason to continue this project of democracy.

So now, for a different type of “platform”-building, could we discuss your book’s appeal to a scrupulously nonpartisan, procedure-prioritizing, principle-affirming platform politics? And given your book’s occasionally expressed fear of a soulless and/or tyrannical technocracy, how might one pursue a platform politics while only tapping the most positive aspects of technocratic governance?

When I refer to platform politics, I do mean to focus less on technological platforms or even on technocratic governance, and more on a particular attitude that a certain style of public campaign has brought back to American politics. Here I’d point to examples like the extraordinary efforts in Michigan to demand and to win a referendum against partisan gerrymandering, the success in New Jersey at blocking partisan gerrymandering, the success in Maine at establishing ranked-choice voting. Those recent successes of platform politics all stem from people not fighting as Republicans or Democrats, but fighting for a democracy that they can believe in — a democracy that actually represents them. And in all three cases, those campaigns did start by stepping away from fierce partisan identity. These platform campaigns all present themselves as citizen campaigns, solving the problems of democracy for everyone.

So when I listen to Katie Fahey, the leader of the Michigan anti-gerrymandering campaign, describe meetings in which people take four or five hours of their night to hammer out precisely how to prevent partisan districting, that doesn’t sound technocratic to me. That sounds like humans coming together to do what we do best — facing down challenges, and figuring out what makes sense for all of us. That’s the kind of inspirational, democratic participation that I think most of us, deep in our hearts, still believe in. Maybe Mitch McConnell or Nancy Pelosi can only see our society through some deeply partisan lens. But 99 percent of Americans still have another perspective, and platform politics speaks to that 99 percent of America.

Again that points to a broader question this book kept posing for me, particularly when it calls for institutional reform more than for individualized censure: how does an institutionally corroded (whether or not morally corrupted) political culture reform itself? What roles does the public play (and not play) in this reform process? And if we end up considering Article V here, could we also bring in prospects for a parallel shadow convention?

I do think we need considerable constitutional change to embed the principles that would make our democracy actually function. I don’t see these changes coming from Congress. Congress won’t structurally reform itself. And if it tried, it probably couldn’t get enough states to pass any constitutional amendments it happened to recommend.

So I do support an Article V convention, which would initiate a process (not controlled by Congress) for proposing amendments to the Constitution. But again, as you said, I don’t think this convention should act on its own. Instead, if the politician-driven process of proposing amendments could take place alongside a citizen-driven shadow convention (say an ambitious set of deliberative polls, that operate first to inform a truly representative sample of Americans, and then to give them a chance to question and to think and to debate), those two simultaneous ways of representing us could complement each other well.

I get why people fear that an Article V convention composed solely of politicians might well do something crazy. But I doubt that a shadow convention of American citizens, represented effectively through deliberative polling, would do anything crazy right-wing or crazy left-wing. Instead I do think we can imagine a convention process that brings out the best both of our long-established representative system, and of 21st-century deliberative polling — with that combination leading to constructive constitutional change. I believe that’s possible. 90 percent of policy wonks and constitutionalists think I’m completely wrong.

Finally then, in terms of not simply calling for, but itself seeking to model a coming to consensus, I think of this book channeling so many different voices as it makes its most basic case for a politics that starts from the question “What can we agree to collectively?” rather than “What do I or my people want?” And here I also return to your rueful formulations of how “we” no longer (if this word ever did) represents us (as anything more than a glib generality), of how we as a collectivity have become ignorant of ourselves (of each other). So for all of the book’s emphasis on representativeness, to what extent do we today need a civic culture proactively building up something like a national identification, so that any American could feel represented by any other American? And how might we best pursue that civic project again in the face both of historically exclusionist claims to American national identity, and of contemporary social/technological pressures pushing us towards an increasingly atomized, even solitary, sense of identity?

I don’t believe that an educational project to build a collective national identity is feasible, in part for those reasons you just mentioned. Instead, I think we should focus on simply getting to the point where most Americans believe that our government represents them, and that it makes its decisions for the right reasons — as opposed to the corrupt or institutionally dysfunctional reasons we’ve discussed today. A big chunk of this book tries to show precisely how the current way of representing “us” (through Gallup polls for instance — all against the background of polarized, antagonizing media) just doesn’t adequately represent us.

When I try to get students to understand this, I’ll say: “Imagine I randomly called you at 4:00 AM, and gave you a pop quiz on constitutional law. How prepared would you feel for that exam?” Total nightmare! Yet we today, as a public, get represented through a process not so different from that pop quiz. Some of us (not many, but still some) get a call from someone asking a bunch of questions about something that there’s little reason to believe anyone really knows anything about. Yet those who answer the phone call give answers (they don’t want to seem stupid!), and those answers get reported as “our” views.

I want this book to ask how we can develop better ways of representing our more reflective and more reasonable selves. When we give exams, we let people prepare, and study, and think, and reflect. That seems fairer than simply calling them and quizzing them. And to the extent that we need “we the people” to speak from inside our political process, we should develop ways of allowing them to speak sensibly — ways that actually give us a reason to have confidence in we the people’s perspective.

That confidence could make us much more hopeful about representative democracy. If we saw, regularly and repeatedly, we the people speaking in an informed and reflective way, we might just have a reason to believe in our collective project again.

Or more pessimistically, if we don’t find a way for us to seem more responsible, then support for democracy will continue to fall. And democracy will continue to fail.

Photo of Lawrence Lessig by Jessica Scranton.