RANKED CHOICE VOTING IN PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS

END THE SPOILER EFFECT ONCE AND FOR ALL

TAKE ACTION WITH US

Would you like to help ensure that our presidential candidates are actually supported by the people?

THE GOAL

THE GOAL

The ability to vote for a candidate who can represent you best is an essential part of a democracy. Yet, because of the two-party system in America, third party candidates are too often “spoilers,” not choices. Voters who favor a third-party candidate face a dilemma: vote for the candidates they prefer, but help elect the candidate they like the least, or vote for the “lesser of two evils”.

This is a wholly unnecessary problem for a 21st century democracy.

Equal Citizens is gearing up to launch a campaign to adopt ranked choice voting for the New Hampshire presidential primaries and for the presidential general election in battleground states.

Stay tuned for more details.

FAQs

What is Ranked-Choice Voting?

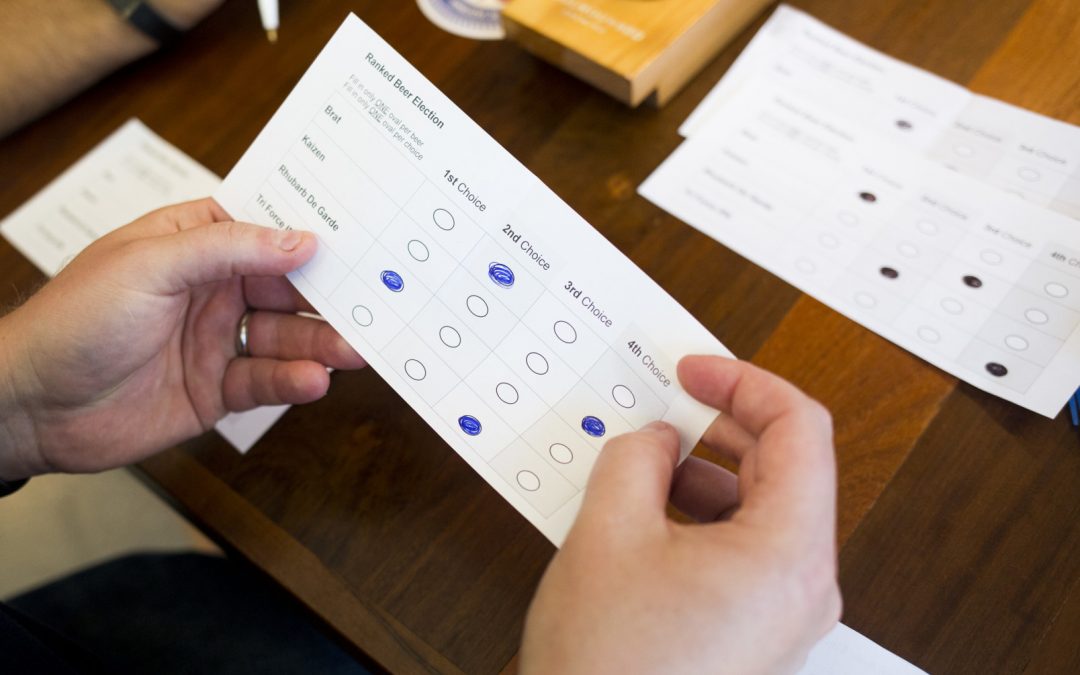

Ranked-choice voting (RCV) is a better way to run elections than the current “one-choice only” system used by almost every state to determine the winner of elections. RCV lets voters rank candidates in their order of preference. A ballot that uses RCV thus does not just ask voters to vote for one candidate but instead gives voters the option to vote for a second-choice, third-choice, and so on. RCV is flexible, so voters are not required to rank their preferences—or, if they do want to rank, they don’t have to rank every candidate running in the race.

In this way, RCV mirrors many everyday activities like, say, listing ice cream flavors in order of preference. With RCV, voters don’t just say whether vanilla, chocolate, or rocky road is their favorite flavor. Instead, they get to choose all three flavors and say which is their favorite, which is second, and which is third. Or, if they want just chocolate, they can stick with chocolate and leave it there. Thus, RCV is simple, flexible, and informative.

Learn more about how RCV works here.

Aren’t delegates already allocated proportionally in many presidential primary races? So what’s the problem?

The current system suffers from two problems: it’s not really proportional, and even one-choice proportional voting is not as good as RCV, because RCV provides more information and reduced strategic voting.

First, the current system is not truly proportional. Rather, both political parties require presidential primary candidates to receive a minimum percentage of votes in order to win any delegates. For the Democratic Party, that threshold is 15 percent, while the Republicans require 10 percent. Thus, proportional allocation occurs only after tens of thousands of votes are tossed out. This means the voters who vote for the candidates that don’t receive the minimum required votes don’t really have a say in the allocation. Moreover, the proportion of delegates are awarded to candidates above the threshold are artificially inflated, because so many votes are discarded before the delegates are actually awarded.

Second, and relatedly, these thresholds create incentives for strategic voting that RCV solves. In the current system, some voters may not vote for their preferred candidate but instead choose their preferred candidate that they think can exceed the threshold. The current system therefore creates many votes are not cast according to the voters’ true preferences. RCV, by contrast, permits voters to be honest about their preferences. If a voter’s first choice candidate is someone that not many others support, that’s okay, because the vote is not simply thrown out. Instead, the ballot is re-used and their vote is given to for their second, third, or fourth choice candidate, depending on how many rounds are needed.

How would ranked choice voting work for presidential primaries?

If New Hampshire implements RCV, political parties would likely use the following method for determining results and allocating delegates. First, New Hampshire would tally voters’ first choices. If a candidate’s vote share is below the threshold needed to receive delegates, those votes get allocated to the voters’ second choice candidate. If there are multiple candidates under the threshold, the procedure is repeated, starting with the lowest vote-getter, until all remaining candidates are above the threshold. The parties then would allocated delegates according to this ranked choice data.

The public record could also show which candidate won the final “instant runoff” when the field is further reduced to the two strongest candidates. Though this wouldn’t affect the delegate allocation, it would offer voters the valuable insight on which candidates are the legitimate frontrunners.

Doesn’t ranked choice voting just help Democrats? Isn’t that what happened in Maine?

In 2018, Maine’s use of RCV did help the Democrat, Jared Golden. The initial round had GOP incumbent Bruce Poliquin winning 46.1 percent of first place votes and Golden receiving 45.9 percent. But that didn’t count voters who voted for third party candidates, who received the other 8 percent of the vote. After re-allocating these third party votes according to those voters’ second and third choices, the final result was Golden’s 50.53 percent to Poliquin’s 49.47 percent.

But here’s the thing: Maine’s system could have been used in at least six other House races and a Senate race in 2018 in which neither candidate hit 50% of the vote. In most of these cases, the use of RCV likely would have favored Republicans. And regardless of who it favors, it would have given more voters the chance to express their views without a strategic worry.

Moreover, the use of RCV in primaries presents no threat of partisan advantage because Democrats only run against Democrats and Republicans against Republicans. While RCV might be more likely to have an effect in the 2020 Democratic primary because there are likely to be more candidates running than the Republican primary, there is every reason to believe that both parties will benefit from it moving forward. As explained above, the Republican Party has long suffered from wasted votes. Since 1992, approximately 15 percent of the vote has been below the 10 percent threshold. And in 2016—the last time there was a competitive race for the Republican presidential nominee—the 10% viability threshold prevented Chris Christie (7.4%), Carly Fiorina (4.1%), and Ben Carson (2.3%) from earning any delegates despite collectively receiving 13.8 percent of the vote. The votes of those who prefered these candidates effective did not count despite comprising a significant portion of the electorate.

In other words, everyone benefits from RCV.

Is there really enough time to pass and then implement such a complex policy in time for the 2020 election?

Yes. The press is eager to start the presidential horse race, but there is still more than a year until the New Hampshire primaries. RCV can easily be implemented in this time frame.

Just look at the example from nearby, in Maine. Maine successfully implemented RCV for their 2018 primary elections with only a few months notice. And even though there were few resources to implement the new rules and educate voters, its use was widely praised and went off without a hitch.

If New Hampshire citizens want RCV, implementation will be the easy part.

Why should ranked choice voting be used for the presidential primary in New Hampshire?

The current “one-choice only” voting method often produces undemocratic primary results, especially with a large number of candidates. That is because both political parties require presidential primary candidates to receive a minimum percentage of votes in order to win any delegates. For the Democratic Party, that threshold is 15 percent, while the Republicans require 10 percent of votes for a candidate to win any delegates. Since only candidates with votes above the threshold are awarded delegates in each state’s primary, multiple candidates could end up receiving a significant share of votes combined without winning any delegates. This vote-splitting is especially likely to occur between a group of ideologically similar candidates.

The use of “one-choice only” ballots for elections with large fields thus often leads to unfair and unrepresentative outcomes. Voters for candidates who do not exceed the delegate threshold cast “wasted” votes that have no effect whatsoever on the primary results, while a candidate who received a minority share of votes above the threshold could end up winning a majority of the state’s delegates. Because New Hampshire, as the first primary state, often has a primary election with a very large field, it is especially vulnerable to vote-splitting under the current system.

The Democratic primary in 2020 is likely to suffer from this problem if the state continues to use “one-choice” only voting. Here could be a dozen or more viable candidates vying to be the Democratic nominee in 2020. Since the Democratic party requires candidates to receive 15% of the vote to be eligible for delegates, it is possible that a substantial percentage of the vote could be cast for candidates below the threshold to win delegates, leading to tens of thousands of “wasted” votes.

This has happened before. In the 1976 New Hampshire Democratic primary, 38.9% of votes were below the threshold. The vote in 1992 and 2004 was similarly fractured leading to 31.52% and 34% of votes wasted. New Hampshire, by implementing RCV, would solve this problem and provide political parties the information they need to prevent an unrepresentative result.

Further, with a large field of candidates, a candidate could “win” that primary with just a small fraction of the overall vote. This happens frequently to both parties: in 2016, Donald Trump won the Republican primary with 35% of the vote, and in 1996 Pat Buchanan won it with only 27% of the vote. On the Democratic side, John Kerry won with 38% of the vote in 2004; Paul Tsongas won with 33% in 1992; and Jimmy Carter won with 29% of the vote in 1976. New Hampshire sets the tone for the rest of primary season—should the New Hampshire voters be very divided in 2020, the New Hampshire primary results will muddy the political waters with the frontrunner winning only a tiny share of the vote.

Are votes really getting thrown out under the current system?

Yes! Votes are wasted far too often in New Hampshire’s presidential primary. In fact, since 1976, approximately 19 percent of the Democratic primary vote has been wasted because of the threshold needed to win delegates. And since 1992, 15 percent of the votes in the New Hampshire Republican primary has been wasted.

The 2016 New Hampshire Republican primary was particularly illustrative of the problem. The 10% viability threshold prevented Chris Christie (7.4%), Carly Fiorina (4.1%), and Ben Carson (2.3%) from earning any delegates despite collectively receiving 13.8% of the vote. The votes of those who prefered these candidates did not count at all. But, if the threshold for Republican candidates were raised to 15%, an astonishing 32.1% of the overall vote would have been “wasted.” And if the threshold had been 16%, Donald Trump would have won all of New Hampshire’s delegates even though he received only 35.2% of the vote.

Given how many candidates might run for the Democratic nomination in 2020, it is possible that more than half the vote could be cast for candidates below the threshold to win delegates, leading to tens of thousands of “wasted” votes.

I’ve never heard of ranked choice voting. Wouldn’t it be too complicated for voters?

No. The evidence shows just the opposite: RCV is simple yet informative. Most voters love it.

Earlier this month, Maine became the first state to decide a federal election using ranked choice voting. Despite having almost no resources to implement new rules and engage in voter education, things went very smoothly. Voter turnout increased from the last midterm election, far fewer voters skipped the RCV races for Congress this year than in recent elections for those same office without RCV, and more than 99.8% percent of voters in the congressional races cast a valid ballot.

The recent success in Maine is not surprising, because RCV actually has a long track record of success in the United States. In total, 18 municipalities across the country use or soon will use RCV, and its earliest implementation was in 1912. Moreover, it is the method of vote counting endorsed by Robert’s Rules of Order when it is impractical to engage in repeated voting and is commonly used internationally for party elections—for instance, all of Canada’s parties pick their leaders using RCV.

For more information about the history of ranked choice voting, check out FairVote’s summary.

Don’t the parties decide how delegates are elected, not the states?

Legally, primaries are conducted by the state government, but it is the political parties that ultimately decide what to do with the results under their own rules for allocating delegates. If RCV were implemented, New Hampshire would conduct and then publish the regular round-by-round count using RCV. The State would turn over all the ballot data over to the parties who can allocate delegates however they want.

If a party wants to use proportional allocation, for instance, they can use the provided data to eliminate candidates sequentially until all remaining candidates are above the threshold for at least one delegate and allocate delegates accordingly. If they want to use winner-take-all, they use the data to award the delegates to the candidate that, after re-tallying of the votes, receives the majority of the votes.

In theory, it is true that the political parties could also choose to ignore the RCV data provided by the state. But that would ignore the will of the voters and the rights of the states to conduct elections that maximize citizen participation, We are confident that the parties will respect the will of the state legislature—and the voters that granted their approval to it—by allocating New Hampshire’s delegates using RCV.

Are there other benefits to adopting RCV?

Yes! RCV improves the quality of the campaign itself. Candidates under RCV have a real interest in broadening their appeal and learning about the views of more voters as they look for common ground rather than division. That is because it is important not only to become the first choice of some voters, but also be the second choice for even those voters who have another favorite. Candidates thus have a strong incentive not to denigrate or insult the candidates whose supporters may still rank them highly on election day.

As a result, political parties would leave the primary not bruised but emboldened. Nominees would not have a year of vicious attacks gifted to their general election opponent. And voters too would benefit, because those voters whose votes are typically wasted would instead be used to impact the election. Needless to say, encouraging more positivity from candidates and voters in our presidential elections would be a welcome change, especially compared to the vicious 2016 election cycle.

Why New Hampshire?

New Hampshire holds the special status as the first in the nation primary. Thus, the state, has an important role—indeed, an obligation—to provide the political parties and the entire nation with as much information as possible. RCV, which provides parties with much more information about voter preferences than the current system, is thus a perfect match for this State.

Moreover, because New Hampshire holds the first primary, it will inevitably be the primary featuring the most candidates. (Many candidates wait until after the Iowa caucus and New Hampshire primary to drop out). Of all the primaries, then, New Hampshire is most vulnerable to wasted votes due to party thresholds.

Last, there is also so much media attention for the first primary contest. If New Hampshire adopted RCV for its primary, RCV would move to the front of many political discussions. Indeed, RCV would go mainstream. This, we hope, would create a critical mass of support needed to spread the idea to many more presidential primaries and state and federal elections across the country.